In Ukraine’s universities, trading bribes for diplomas

- Iuliia Mendel for Politico.eu

- 24 авг. 2016 г.

- 4 мин. чтения

“I’ll never forget what he said when he found what he was looking for: ‘Now I see it. Your work is good.’ ”

By

IULIIA MENDEL

1/30/16, 6:00 AM CET

KIEV, Ukraine — I hadn’t paid a bribe in my home country until it was time to defend my doctoral dissertation. I tucked $200 in page six of my manuscript before I handed it to my adviser. His department colleagues insisted on the illicit practice when I complained that my professor refused to touch my thesis for more than three weeks. The deadline was approaching.

Now I watched as my esteemed professor of modern Ukrainian literature thumbed through the pages. My face turned red with shame but I’ll never forget what he said when he found what he was looking for: “Now I see it. Your work is good.”

My experience defending my dissertation in the best university in Ukraine, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kiev, an institution recognized throughout the world, was humiliating but by no means unique. While tuition costs for higher education are very democratic in Ukraine — averaging less than $1,000 per academic year — the hidden costs are steep.

A fellow student from Mariupol in eastern Ukraine never questioned the necessity of bribes. Her experience taught her that corruption was the only way to graduation. During the four years she spent writing her Ph.D. thesis, she spent an unimaginable amount of money on bribes. She paid her adviser $1,000 to thank him for his mentoring. The same sum went to another professor for editing her papers, even though this was part of his regular duties.

This is the fate of nearly every Ukrainian student: Victoria, a student at the university’s journalism institute, knew she wouldn’t pass her junior year exam without paying her professor $300. Katya, in the medical program, saved on food to afford to pay $50 for every mark during the semester. A few male students from Kharkiv knew they could simply pay for their diplomas and skip the exams altogether.

Robert Orttung, an expert on post-Soviet systems of corruption at George Washington University, spent two months traveling Ukraine with a team of researchers and asked regular people where they most frequently encountered corruption. Education ranked third on the list, after the medical system and the police.

“The main reason for education’s prominence as an area of corruption is that often professors and teachers receive small salaries so they have a need for more income,” Orttung wrote in an email. “They have to extract money where they can in order to survive and that basically amounts to demanding bribes.”

Both Ukraine’s president and prime minister have held up education reform as a success story. Times Higher Education called Minister of Education Serhiy Kvit “perhaps Ukraine’s most successful minister” for pushing through more than half of his reform program in less than two years.

Last summer, the parliament passed a new law on higher education to give universities more autonomy, including control over their own finances. The goal was to encourage private investment, fundraising and even the creation of endowments, and to sweep away the top-down Soviet model of university management.

“We need a new post-Soviet model of leadership, in which teams play a larger role in universities and different levels of management involve more people in their decisions,” said Kvit in a recent interview. The minister knows what he’s talking about, but whether he has the power to change the system is another question.

I attempted to enter my alma mater last December without a student ID, and with some old school cunning and sweet talk, I managed to slip by the guards and walk the familiar university halls. Up on the walls are framed portraits, in the style of North Korean party officials, of the university’s professors, most of them familiar faces from my dissertation defense four years ago.

Almost every university worker is a relative or a friend. Once, the head of my institute agreed to employ a woman who had recently had a child and didn’t want to work, but still wanted a paycheck. It was a favor among friends.

It’s hard to imagine that anyone will be successful in changing the system until the ruling educator-godfathers are replaced. They will only be unseated when bribes, a major source of their revenue, are stopped.

The state’s educational apparatus is mostly covered from the state budget and too gigantic to thrive by legal means. There are 664 higher education institutions in Ukraine; 260 more universities than Germany, even though Ukraine’s population is half the size of Germany’s. This figure does not include the 139 universities that the ministry of education closed last year because of license discrepancies.

The new education reform law requires all universities and colleges to post their financial documents online, but only a dozen have done this, according to the independent, non-partisan analytical center CEDOS.

“Since people are willing to pay for these services, everyone would be better off if the system could be made more formal and transparent, so that instead of paying bribes people [would] pay taxes and the state could fund services,” Orttung said. “Of course, few want to pay taxes because they do not trust the state to provide good services.”

But curtailing bribery in higher education is not in fact a government priority, according to the administration’s National Reform Council. The education ministry conducted lectures on civil responsibility, and required that professors create special anti-corruption departments to police their own departments. The results speak for themselves: so far, the ministry of education only learned about one corrupt academic. A senior lecturer was accused of taking a $100 bribe. He received a two year probation.

When graduating students defend their dissertations in Shevchenko University’s linguistics department, they’re required, as a group, to cover the expenses of a scientific review council — 26 professors who come from all over Ukraine to approve university degrees in Kiev. Students are expected to cover their tickets, taxis, a per diem and center city hotel accommodations, as well as graduation lunches and dinners supplied with top-shelf alcohol and catered exclusively by the university canteen.

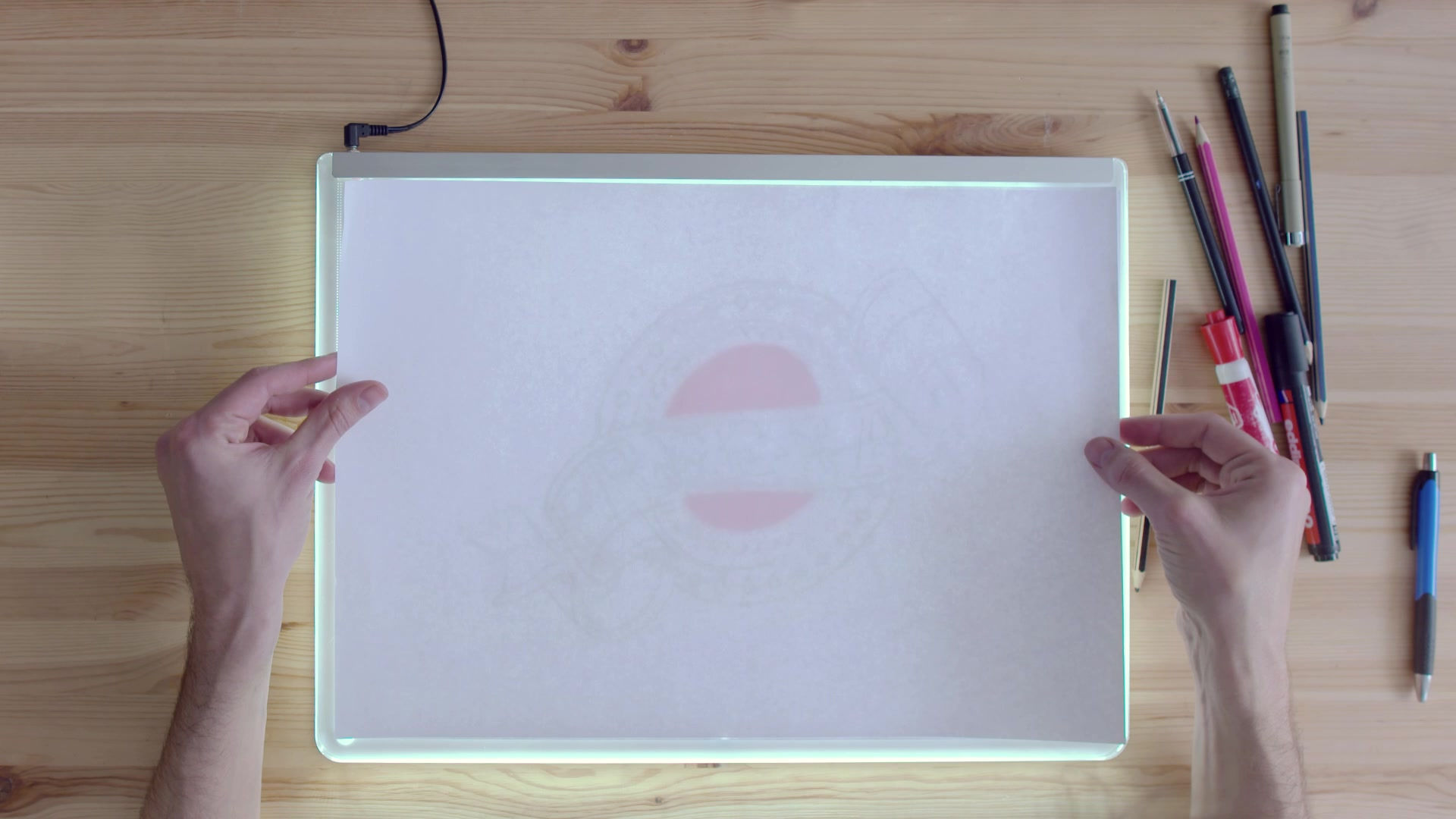

Despite her fears, my Mariupol colleague’s defense was brilliant. Only one professor out of 26 came to listen to her. She defended in front of him and a girl with a tape recorder. It was growing dark, and the light in the hall remained switched off, as always, to save money on the electric bill.

Iuliia Mendel is a 2015 fellow of the World Press Institute.

Комментарии